| 【开放获取数据库-古典学】Ancient Greek Theater 希腊悲剧 教学参考 |

| (发布日期: 2016-03-03 15:37 阅读:次) |

|

网址:http://www.reed.edu/humanities/110tech/theater.html#timeline

Ancient Greek Theater The theater of Dionysus, Athens (Saskia, Ltd.) This page is designed to provide a brief introduction to Ancient Greek Theater, and to provide tools for further research. Click on any of the following topics to explore them further. 1. Timeline of Greek Drama 2. Origins of Greek Drama 3. Staging an ancient Greek play 5. Structure of the plays read in Humanities 110 6. English and Greek texts of the plays for word searching. 7. Bibliography and links to other on-line resources for Greek Tragedy 1. Timeline of Greek Drama Although the origins of Greek Tragedy and Comedy are obscure and controversial, our ancient sources allow us to construct a rough chronology of some of the steps in their development. Some of the names and events on the timeline are linked to passages in the next section on the Origins of Greek Drama which provide additional context. (Works in bold are on the Hum 110 syllabus) 7th Century BC c. 625 Arion at Corinth produces named dithyrambic choruses. 6th Century BC 600-570 Cleisthenes, tyrant of Sicyon, transfers "tragic choruses" to Dionysus 540-527 Pisistratus, tyrant of Athens, founds the festival of the Greater Dionysia 536-533 Thespis puts on tragedy at festival of the Greater Dionysia in Athens 525 Aeschylus born 511-508 Phrynichus' first victory in tragedy c. 500 Pratinus of Phlius introduces the satyr play to Athens 5th Century BC 499-496 Aeschylus' first dramatic competition c. 496 Sophocles born 492 Phrynicus' Capture of Miletus (Miletus was captured by the Persians in 494) 485 Euripides born 484 Aeschylus' first dramatic victory 472 Aeschylus' Persians 467 Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes 468 Aeschylus defeated by Sophocles in dramatic competition 463? Aeschylus' Suppliant Women 458 Aeschylus' Oresteia (Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, Eumenides) 456 Aeschylus dies c. 450 Aristophanes born 447 Parthenon begun in Athens c. 445 Sophocles' Ajax 441 Sophocles' Antigone 438 Euripides' Alcestis 431-404 Peloponnesian War (Athens and allies vs. Sparta and allies) 431 Euripides' Medea c. 429 Sophocles' Oedipus the King 428 Euripides' Hippolytus 423 Aristophanes' Clouds 415 Euripides' Trojan Women 406 Euripides dies; Sophocles dies 405 Euripides' Bacchae 404 Athens loses Peloponnesian War to Sparta 401 Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus 4th Century BC 399 Trial and death of Socrates c. 380's Plato's Republic includes critique of Greek tragedy and comedy c. 330's Aristotle's Poetics includes defense of Greek tragedy and comedy 2. Origins of Greek Drama Ancient Greeks from the 5th century BC onwards were fascinated by the question of the origins of tragedy and comedy. They were unsure of their exact origins, but Aristotle and a number of other writers proposed theories of how tragedy and comedy developed, and told stories about the people thought to be responsible for their development. Here are some excerpts from Aristotle and other authors which show what the ancient Greeks thought about the origins of tragedy and comedy. Aristotle on the origins of Tragedy and Comedy

Stories about Cleisthenes, Sicyon, and Hero-drama

Stories trying to explain why, if tragedy originated from Dithyrambs sung in honor of Dionysus, not all tragedies were about Dionysus ("Nothing to do with Dionysus": (ouden pros ton Dionuson)

Stories about Thespis the Athenian playwright

3. Staging an ancient Greek play Attending a tragedy or comedy in 5th century BC Athens was in many ways a different experience than attending a play in the United States in the 20th century. To name a few differences, Greek plays were performed in an outdoor theater, used masks, and were almost always performed by a chorus and three actors (no matter how many speaking characters there were in the play, only three actors were used; the actors would go back stage after playing one character, switch masks and costumes, and reappear as another character). Greek plays were performed as part of religious festivals in honor of the god Dionysus, and unless later revived, were performed only once. Plays were funded by the polis, and always presented in competition with other plays, and were voted either the first, second, or third (last) place. Tragedies almost exclusively dealt with stories from the mythic past (there was no "contemporary" tragedy), comedies almost exclusively with contemporary figures and problems. In what follows, we will run through an imaginary (but as far a possible, accurate) outline of the production of a Greek tragedy in 5th century BC Athens from beginning to end. The outline will bring out some of the features of creating and watching a Greek tragedy that made it a different process than it is today. Staging a play. 4. Greek Theaters

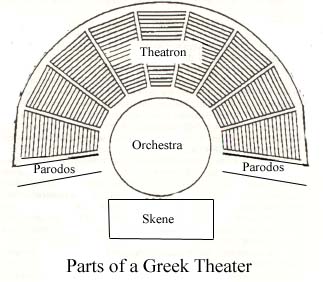

Greek tragedies and comedies were always performed in outdoor theaters. Early Greek theaters were probably little more than open areas in city centers or next to hillsides where the audience, standing or sitting, could watch and listen to the chorus singing about the exploits of a god or hero. From the late 6th century BC to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC there was a gradual evolution towards more elaborate theater structures, but the basic layout of the Greek theater remained the same. The major components of Greek theater are labled on the diagram above. Orchestra: The orchestra (literally, "dancing space") was normally circular. It was a level space where the chorus would dance, sing, and interact with the actors who were on the stage near the skene. The earliest orchestras were simply made of hard earth, but in the Classical period some orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials. In the center of the orchestra there was often a thymele, or altar. The orchestra of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was about 60 feet in diameter. Theatron: The theatron (literally, "viewing-place") is where the spectators sat. The theatron was usually part of hillside overlooking the orchestra, and often wrapped around a large portion of the orchestra (see the diagram above). Spectators in the fifth century BC probably sat on cushions or boards, but by the fourth century the theatron of many Greek theaters had marble seats. Skene: The skene (literally, "tent") was the building directly behind the stage. During the 5th century, the stage of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was probably raised only two or three steps above the level of the orchestra, and was perhaps 25 feet wide and 10 feet deep. The skene was directly in back of the stage, and was usually decorated as a palace, temple, or other building, depending on the needs of the play. It had at least one set of doors, and actors could make entrances and exits through them. There was also access to the roof of the skene from behind, so that actors playing gods and other characters (such as the Watchman at the beginning of Aeschylus' Agamemnon) could appear on the roof, if needed. Parodos: The parodoi (literally, "passageways") are the paths by which the chorus and some actors (such as those representing messengers or people returning from abroad) made their entrances and exits. The audience also used them to enter and exit the theater before and after the performance. Greek Theaters Click here to explore more about Greek theaters in Perseus, with descriptions, plans, and images of eleven ancient theaters, including the Theater of Dionysus in Athens, and the theater at Epidaurus. 5. Structure of the plays read in Humanities 110 The basic structure of a Greek tragedy is fairly simple. After a prologue spoken by one or more characters, the chorus enters, singing and dancing. Scenes then alternate between spoken sections (dialogue between characters, and between characters and chorus) and sung sections (during which the chorus danced). Here are the basic parts of a Greek Tragedy: a. Prologue: Spoken by one or two characters before the chorus appears. The prologue usually gives the mythological background necessary for understanding the events of the play. b. Parodos: This is the song sung by the chorus as it first enters the orchestra and dances. c. First Episode: This is the first of many "episodes", when the characters and chorus talk. d. First Stasimon: At the end of each episode, the other characters usually leave the stage and the chorus dances and sings a stasimon, or choral ode. The ode usually reflects on the things said and done in the episodes, and puts it into some kind of larger mythological framework. For the rest of the play, there is alternation between episodes and stasima, until the final scene, called the... e. Exodos: At the end of play, the chorus exits singing a processional song which usually offers words of wisdom related to the actions and outcome of the play. Click here to see an analysis of the structure of the plays read in Humanities 110. 6. English and Greek texts of the plays for word searching. This page allows you to find passages in the any of the plays in either Greek or English. In sections H and I there are links which allow you to search for particular English or Greek words in the text of any of the plays. A. Agamemnon B. Libation Bearers C. Eumenides D. Antigone E. Oedipus the King F. Bacchae G. Clouds H. Search for English word in any of the plays. To search for the occurance(s) an English word in one of the plays, click on the above, and type in the English word in the box marked "Look for:"; then type in the name of the author of the play (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, or Aristophanes) in the box marked "Show results for". The search will turn up the occurance of the word you have requested in all of the plays of the author you have typed in. I. Search for Greek word in any of the plays. You do not have to know ancient Greek to use this helpful resource. The Greek word search program allows you to type in an English word, and then gives you all of the Greek words that have that English word as part of the definition. You can then search for those Greek words in the Greek texts you are interested in. This is very helpful, because it allows you to be less dependent on the English translation when you are searching for a word or concept in the Greek text. For example, if you are exploring the issue of "justice" in one of the plays, you can find out what the Greek words are that have "justice" as part of their definition, and then search for those words directly in the Greek text of the play. 7. Links to other on-line resources for Greek Theater and a brief bibliography A. Bibliography for further reading Books in the Reed Library that provide helpful approaches to Greek Tragedy include: General Books Goldhill, S. Reading Greek Tragedy (1986) Heath, M. The Poetics of Greek Tragedy (1987) Knox, B. Word and Action (1979) Lesky, A. Greek Tragic Poetry (1983) Rehm, R. Greek Tragic Theatre (1992) Segal, C. Interpreting Greek Tragedy: Myth, Poetry, Text (1986) Taplin, O. Greek Tragedy in Action (1978) Vernant, J.P., and Vidal-Naquet, P. Tragedy and Myth in Ancient Greece (1981) Vickers, B. Towards Greek Tragedy (1973) Winkler, J. and Zeitlin, F. Nothing to Do with Dionysus? (1990) Origins of Greek Drama Burkert, W. "Greek Tragedy and Sacrificial Ritual." Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 7 (1966): 87-121. Lesky, A. Greek Tragic Poetry (1983). Chapter 1: "Problems of Origin." Pickard-Cambridge, A.W. Dithyramb, Tragedy, and Comedy (1927) ________, second edition by Webster, T.B.L. (1962) Winkler, J. "The Ephebes' Song: Tragoîdia and Polis." reprinted in Nothing to Do with Dionysus? (1990) Aeschylus Goldhill, S. Language, Sexuality, Narrative: The Oresteia (1984) Lebeck, A. The Oresteia: A Study of Language and Structure (1971) Rosenmeyer, T. The Art of Aeschylus (1982) Taplin, O. The Stagecraft of Aeschylus (1977) Winnington-Ingram, R.P. Studies in Aeschylus (1983) Sophocles Blundell, M.W. Helping Friends and Harming Enemies: A Study in Sophocles and Greek Ethics (1989) Edmunds, L. Oedipus: The ancient Legend and its Later Analogues (1985) Gardiner, C.P. The Sophoclean Chorus (1987) Gellie, G. Sophocles: A Reading (1972) Knox, B. The Heroic Temper (1964) Knox, B. Oedipus at Thebes (1957) Scodel, R. Sophocles (1984) Segal, Charles Tragedy and Civilization: An Interpretation of Sophocles (1981) Winnington-Ingram, R.P. Sophocles: An Interpretation (1980) Euripides Burian, P., ed. Directions in Euripidean Criticism (1985) Collard C. Euripides (Greece and Rome Surveys in the Classics n. 14) (1981) Foley, H. Ritual Irony: Poetry and Sacrifice in Euripides (1985) Halleran, M. Stagecraft in Euripides (1985) Michelini, A.N. Euripides and the Tragic Tradition (1987) Segal, C. Dionysiac Poetics and Euripides' Bacchae (1982) Segal, E., ed. Euripides Velacott, P. Ironic Drama: A Study of Euripides (1975) Winnington-Ingram, R. Euripides and Dionysus: An Interpretation of the Bacchae (1948) Aristophanes Cartledge, P. Aristophanes and His Theatre of the Absurd (1990) Dover, K.J. Aristophanic Comedy (1972) Henderson, J. The Maculate Muse: Obscene Language in Atic Comedy. 2nd edition. (1991) Henderson, J. "The Demos and the Comic Competition", in J. Winkler and F. Zeitlin, eds, Nothing to Do with Dionysus? (1990) Konstan, D. Greek Comedy and Ideology (1995) MacDowell, D. Aristophanes and Athens (1995) McLeish, K. The Theatre of Aristophanes. London, 1980. Nussbaum, M. "Aristophanes and Socrates on learning practical wisdom", Yale Classical Studies 26 (1980) 43-97. Redfield, J. "Drama and Community: Aristophanes and Some of His Rivals", in J. Winkler and F. Zeitlin, eds, Nothing to Do with Dionysus? (1990) Taplin, O. Comic Angels and Other Approaches to Greek Drama through Vase-Paintings. Oxford: 1993. Ussher, R.G. Aristophanes (Greece and Rome New Surveys in the Classics, 13). Oxford, 1979. Whitman, C.H. Aristophanes and the Comic Hero. Cambridge, MA., 1964. This page developed by Walter Englert for Hum110 Tech. |

首页

首页